Python is an interpreted, high level, a general purpose programming language which was initially designed by Guido van Rossum in 1991. Python has evolved over the years and is one of the top 5 popular programming languages as of May 2019, as per TIOBE index. Code readability, simplified syntax, compatibility with many operating systems, robust libraries makes the language widely used for creating great applications.

While Python is widely used nowadays, it’s also better to know a language in terms of its disadvantages as well. No language is perfect, some are better than others.

Weak spots of Python

- Python is not a widely used language for mobile computing. The language is also not present in web development browsers. Python is hard to secure, and that’s why it is not in browsers. Source: Article

- Susceptible to run time errors, since Python is dynamically typed language; it only translates and type-checks code it’s executing on. A programming language is said to be dynamically typed, or just ‘dynamic’, when the majority of its type checking is performed at run-time as opposed to at compile-time

Interpreted: Code translated into machine language instructions on the fly, during execution

Typing: This is process when data types are checked. Two categories:

Static: Data types checked before run time

Dynamic: Data types are checked on the fly, during execution

def dynamic(a):

if a > 0:

print(‘Am dynamically typed’)

else:

print(“3”+5)

dynamic(2)

In the above code snippet, the else block never executes, because the valued passed to the function will go to the `if` block always. If the value passed is less than 1, the else block is executed and will raise an error as below

def dynamic(a):

if a > 0:

print(‘Am dynamically typed’)

else:

print(“3”+5)

dynamic(-1) # Calling function and passing value 2.

>» python .\static_dynamic_typed.py

Traceback (most recent call last):

File “.\static_dynamic_typed.py”, line 6, in

dynamic(-1) # Calling function and passing value 2

File “.\static_dynamic_typed.py”, line 5, in dynamic

print(“3”+5)

Making it simple, the type checking does not happen in Python until the line never executes.

3. Does not have access modifiers or by default, all the variables and member functions of a class are public in Python. It is allowed to access an instance variable from outside. Python uses single underscore prefix for a variable to denote a private method. It does not change the access privilege as in languages like JAVA or C#

4. Speed limitations because Python code is executed line by line. But when python is interpreted, it often results in slow execution than other popular languages.

5. The simplicity of Python programming language syntax makes programmer more of a Python person, because of which sometimes shifting to a new language will be harder

Having canvassed about the fine points and weak spots of Python, it’s time to be thick with the language.

Python Bytes

Python is a programming language as well as a scripting language. Some of the features of Python are listed below:

- Object Oriented

- Free ( Open Source)

- Portable

Quick Note: Python implementation consists of an interpreter. However, some Python implementations, do consist of just-in-time compiler that will compile Python byte code into native machine code

Source code is translated into byte code, which is then run by a Python virtual machine. The code is automatically compiled but then interpreted.

There are two major versions of Python: 2.x and 3.x. Both are quite different. The samples shown in this article are using the 3.x version of Python. 3.x is a non-backwards compatible version of Python and hence it is recommended to use the 3.x version of Python when building a new application. Below is the most well-known change between Python 2.x and 3.x

# Python 2.x syntax below:

>» print ‘Hello World’

# Python 3.x syntax below:

>» print(‘Hello World’)

_print_is a statement in Python 2.x

_print_is a function in Python 3.x

This article would discuss some of the useful stubs while working with Python language. It’s assumed that readers have basic knowledge of programming and Python language. The inspiration for this article was of the fact of writing readable and cleaner code. A later series of this article will be followed.

Some of the tips & tricks while using Python language are as below:

Built-Ins

The Python language has a set of functions readily available for use. These functions are called built-in functions. Let’s look at some of the important built-in functions that will come handy.

- dir() function

This function returns a list of valid attributes for the given object. This is a great function to determine the available attributes of an object.

The syntax of dir() function is dir([object]). It takes only one argument.

In the above window, for an integer value assigned to x, we get a list of methods that can be used for numeric operations. The output of the code below shows, for a string value assigned to y, we get a list of methods that can be used for string operation.

2. type() function

This function returns the type of an object.

Syntax: type(object)

>» type(x)

<class ‘int’>

>» type(y)

<class ‘str’>

It’s a useful function if we want to process only a specific type of elements.

3. help() function

This function is used to get the documentation of a specified module, class, functions. This method is generally used with Python interpreter console.

Syntax: help([object])

>» help()

Welcome to Python 3.7’s help utility!

If this is your first time using Python, you should definitely check out

the tutorial on the Internet at https://docs.python.org/3.7/tutorial/.

Enter the name of any module, keyword, or topic to get help on writing

Python programs and using Python modules. To quit this help utility and

return to the interpreter, just type “quit”.

To get a list of available modules, keywords, symbols, or topics, type

“modules”, “keywords”, “symbols”, or “topics”. Each module also comes

with a one-line summary of what it does; to list the modules whose name

or summary contain a given string such as “spam”, type “modules spam”.

help>

# Observe the prompt have changed from `»>` to ‘help>’

help> keywords

Here is a list of the Python keywords. Enter any keyword to get more help.

False class from or

None continue global pass

True def if raise

and del import return

as elif in try

assert else is while

async except lambda with

await finally nonlocal yield

break for not

#type `quit` to come out of help window

We can also get the help documentation directly from the Python console by passing a parameter to help() function.

>» help(print)

Help on built-in function print in module builtins:

print(…)

print(value, …, sep=’ ‘, end=’\n’, file=sys.stdout, flush=False)

Prints the values to a stream, or to sys.stdout by default.

Optional keyword arguments:

file: a file-like object (stream); defaults to the current sys.stdout.

sep: string inserted between values, default a space.

end: string appended after the last value, default a newline.

flush: whether to forcibly flush the stream.

Opening and Closing files in Python

Python supports file handling and allows users to read and write to files, along with many other file operations. File handling in Python requires no importing of modules.

Syntax: open('<name of file>','mode')

fileObj = open(’test.txt’) # Default open mode is read

fileObj.close() # Once you open the file, you have to close

It is really important to close the file, once the action on the file is completed. This makes that there no further problems like resource leaks and may cause the system to slow down and crash.

In Python, this can be brought to fruition using context managers, which can automatically release resources after use. The sample code snippet is as below:

with open(’test.txt’,‘r’) as file:

print(file.read())

In simple terms, Python calls __enter__ and __exit__ methods to an object, which functions as a context manager. These methods will be called by Python at the right time, during resource management.

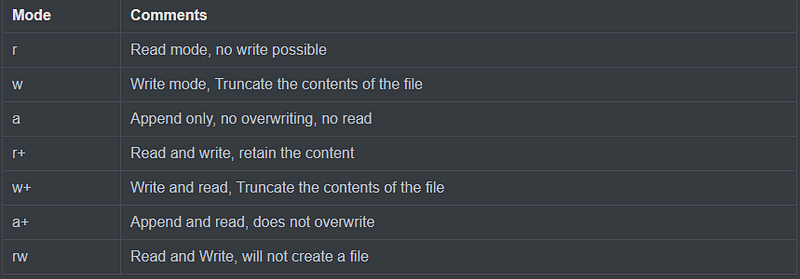

Different file opening modes are as follows:

- seek() and tell() function

When a file is opened for reading in Python, the file handle points to the beginning of the file. As we read the first line the pointer always points to the place where we ended the reading and the next read will start from there.

This happens unless we tell the file handler to move.

The tell() the function will return the current location of the pointer and the seek() the function will move the pointer.

Syntax: seek(offset,whence)

Offset : Can take negative, 0 or positive values. A positive offset will move the file pointer forward, a negative offset will move the file pointer backwards.

Whence: This argument is optional and takes the below values:

- Value 0 (default ): Beginning of file

- Value 1 Current file position

- Value 2 End of file

Syntax: tell()

fileobj = open(’test.txt’)

x = fileobj.tell()

print(fileobj.tell())

line = fileobj.readline()

while line:

print(line)

#print(fileobj.seek(x))

fileobj.seek(x)

print(fileobj.readline())

#print(line)

x = fileobj.tell()

print(fileobj.tell())

line = fileobj.readline()

fileobj.close()

The above code snippet reads a file and uses tell() and seek() functions to play around with file handler positions.

2. Ternary Conditional Operators

These are operators that evaluate something based on a condition being true or false. This simply allows to test a condition in single line replacing the multiline if-else statement making code short and readable.

Syntax: [on_true] if [expression] else [on_false]

Let’s look at a sample code snippet with if-else condition:

a,b = 10, 20

if a < b:

min = a

else:

min = b

print(min)

# this would return the output of 10

The above code can be written in a single line as below:

a,b = 10, 20

min = a if a < b else b

print(min)

# this would return the output of 10

3. enumerate() Function

This function is used to iterate through a list while keep tracking of the items’ indices. Usually the code to print the indices of the items in the list is as below:

pets = (‘Dogs’, ‘Cats’, ‘Turtles’, ‘Rabbits’)

index = 0

for pet in pets:

print(index,pet)

index += 1

# the output is as follows:

0 Dogs

1 Cats

2 Turtles

3 Rabbits

With enumerate():

pets = (‘Dogs’, ‘Cats’, ‘Turtles’, ‘Rabbits’)

for i, pet in enumerate(pets):

print (i, pet)

# the output is as follows:

0 Dogs

1 Cats

2 Turtles

3 Rabbits

The output not only print out contents of the tuple, but also their index orders. You can also pass in a start value, if you don’t want to start the index from 0.

4. zip() funtion

This function take in a pair of streams and gives a pair of streams. It stops when the shortest sequence is exhausted. Like a Ziploc in the real world zip() function acts as a container to hold values. It evaluates from left to right.

The following code snippet gives more information on zip() function:

numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

letters = [‘a’, ‘b’, ‘c’, ’d’, ’e’]

for num,alpha in zip(numbers,letters):

print(’{} number is related to {}’.format(num,alpha))

# the output is as follows

1 number is related to a

2 number is related to b

3 number is related to c

4 number is related to d

5 number is related to e

5. Single underscore “_” variable

Sometime “_” ( single underscore ) is used as a variable name in Python. This denotes it’s a throwaway variable and will not be used in the Python programs. It is mainly used to ignore value when unpacking.

a, _ = (1,2)

#Tuple unpacking

print(a)

# the output will be

1

In the above case, if the values are unpacked in the form of a, b = (1, 2) and variable b is never used in the program, some IDE’s will complain about an information message Variable declared, but not used . Declaring a single underscore variable solves this issue.

“_” ( single underscore ) is also used after a variable name, this is to avoid conflict between a Python keyword and variable we use.

Different scenarios of unpacking values are as follow:

# Too many values to unpack

>» a, b = (1,2,3,4,5)

Traceback (most recent call last):

File “”, line 1, in

ValueError: too many values to unpack (expected 2)

In the above case we have two options:

- Assign the first two values to a and b and rest to c as below:

>» a, b, *c = (1,2,3,4,5)

>» print(a)

1

>» print(b)

2

>» print(c)

[3, 4, 5]

2. Ignore the rest of the values using a single underscore:

>» a, b, *_ = (1,2,3,4,5)

>» print(a)

1

>» print(b)

2

3. Saving the first two values in a and b, rest of the values up to the last one in c and the last value in d

>» a, b, *c, d = (1,2,3,4,5)

>» print(a)

1

>» print(b)

2

>» print(c)

[3, 4, 5]

>» print(d)

5

# ignore the rest of the values up to `d`

>» a, b, *_, d = (1,2,3,4,5)

Conclusion

Though there are lot of life hacks, when using Python programming this article tried to cover some of them. More information on these great life hacks can be accessed at below sites:

Use the below sites for trying out Python code samples online:

Feel free to send in your suggestions Sunil Jacob